Hidden Presence - REFLECTIONS ESSAY # 1 by Dr Shawn Sobers,

University of the West of England, Bristol

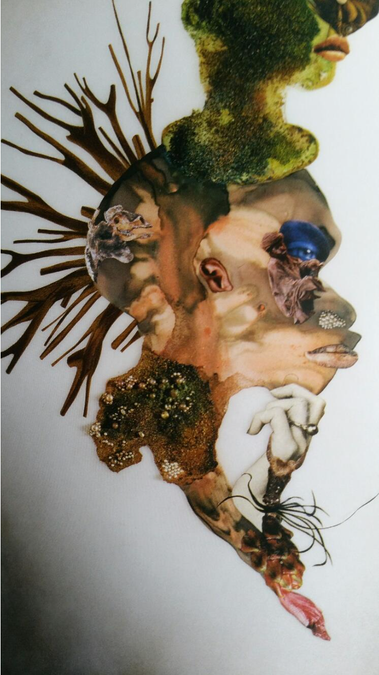

This image was made by a young person from a school in Chepstow as part of the Hidden Presence project with artist facilitator Eva Sajovic. The project used the life of former enslaved African Nathaniel Wells as the starting point for exploring place and identity in challenging ways. I don’t know the name of the young artist or what conversations were going on when they made it, or if there were any visual references they had in mind when it was created. It immediately reminded me of anthropological photography from the late 19th early 20th century, and their brutal forensic approach to portrait photography, the whole purpose of which was the “scientific” specimen analysis of human types. The montage effect of this image however gives it a much more contemporary feel, a composite that visually argues against the fallacy of the scientific conceit of using photography to further a racist ideology. This montage portrait is unapologetically modern,

a blend of ethnicities, cultures, references, and it could be described as (dare I say it) a post- racial representation. The fragmentary style and blank gaps speaks of how human beings are more complex than we allow ourselves and others to be. Beneath our surface skin we are a mass of cultural contradictions, influences and even DNA.

Is this image the artist’s representation of Nathaniel Wells (a man with no lasting portrait in existence), or is it a more generalised portrait of us all? We can see that the eyes and possibly neck are from an African heritage person, and the hair, ears and mouth possibly being European. The game of identifying the ethnic patch may be a futile exercise, but the whole point of entering that dialogue in relation to the Nathaniel Wells story is partly the point of the whole enterprise – who are we anyway? What makes us the people we think we are?

One of the beauties of doing projects in schools is seeing that many of the art works produced by the young people can be continuations of conversations that began with other more established artists that came before them, without the young people even being aware they are entering a wider dialogue. Art becoming an entry point into a broader set of considerations, negotiations and ideas that allows the young people to think beyond their immediate set of personal concerns, even if only for the duration of making the art work.

For example, see how the above image by the young artist from South Wales, relates to the work of African American artist Romare Bearden, and Kenyan born artist Wangechi Mutu, (see below).

Flights and Fantasy, 1970, Romare Bearden

You are always on my mind,2007, Wangechi Mutu

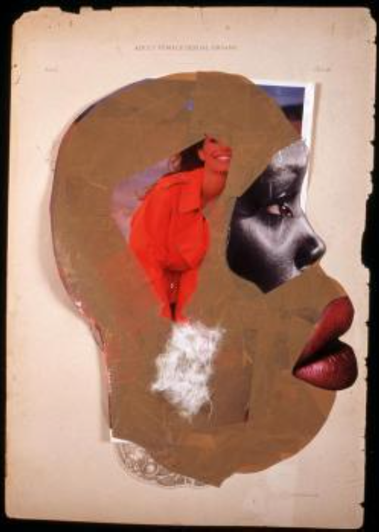

Adult Female Sexual Organs,2005, Wangechi Mutu

Romare Bearden (whose entire career, spanning more than 50 years, explored different aspects of African American culture) was so light in complexion that he was offered opportunities on condition that he ‘passed for white’, though he refused.

The above image ‘Flights of Fantasy’ is a composite body made up different fragments of ethnicities, the face however containing no detail, but unmistakable in its ethnic depiction, the face being the primary carrier and signifier of ethnic identity.

Wangechi Mutu’s images are similarly a collation of pieces to make up a whole. In ‘Adult Female Sexual Organs’, the base of an illustration of a woman’s reproductive organs are built upon with parcel tape and magazine cut-outs to create the face of a Black woman with the

archetypal Caucasian beauty on her mind. The image ‘You are always on my mind’ also carries the weight of social concerns on the body of the Black female, including the figure of a street beggar, in contrast with elegant jewelled white hand, precious beads, and the carcass of an animal. Mutu says of her work, “Females carry the marks, language and nuances of their culture more than the male. Anything that is desired or despised is always placed on the female body.” The montage face communicates an idea then, that individuals are not divorced from their (our) surroundings or situations, and become a part, not apart, of who we are.

The image then of Nathaniel Wells (or not) above, is similar. It challenges us with the question, what does it matter what the man looked like, when all we really know are the surroundings and situations he lived in. Nathaniel’s life was a mass of contradictions and that is what we are faced with. This portrait is no less true than a photograph of the man himself. We would not be able to reach into a photograph of Nathaniel to see the inner workings of his brain or see his dreams and fears. That is the same for any portrait. I have never believed the conceit that we can tell anything of the character of a person through a portrait photograph, with the eyes being the ‘window to the soul’. Portrait photographs are records of what that person was doing at that captured moment in time, not a second before, and not a second afterwards.

In an age where all of the world’s information is at our fingertips, it is humbling to know that we will never know some things. As fascinating a character that Nathaniel Wells is, we will never know what his face looked like or truly understand his motivations. He was a contradiction, as we all are, and this image reminds us of that, whether we choose to like it or not.

• • •

Hidden Presence - REFLECTIONS ESSAY # 2 by Dr Alex Southern, Wales Centre for Equity in Education, University of Wales Trinity Saint David

When I look at the artwork created by the young people on the Hidden Presence project, I’m immediately drawn to the stills which have been taken from archive footage and animated to create new, digital, moving images. One in particular catches my eye. The gif animation comprises two layers of moving image. One depicts workers on a sugar plantation; the other shows a young boy seated across the table from an older lady, drinking cups of tea.

The animation is thought-provoking and sharp, and for me, it raises the sometimes contentious issue of the place of archive film – and archives more widely – in re/presenting histories through images of the past. I do not know the provenance of the films, nor have I spoken with the young people of Caldicott School to ask what their intentions were in making the animation. I must take the artwork as it is now, bringing my own assumptions, prior knowledge and cultural ‘baggage’ to my interpretation of what I see.

My reflection on the animation begins with a reflection on notions of history.

Hidden Presence, film still, Caldicott School

The term ‘history’ is perhaps ambiguous since it implies two distinct concepts: the past; and the writing, study and discussion about the past, or ‘historiography’ as it is also termed. While there are a finite number of past events, their potential interpretation is infinite since different people will offer their own interpretation of these events through the way in which they choose to read them, juxtapose them with others, insert them within historical contexts or create new contexts and use them to establish new narratives about the past. This in turn means that there is an infinite variety of narratives about the past, since we can each tell the story of an event in different ways. I might go to Paris and refuse to get in the lift of the Eiffel Tower because I don’t like heights. My friend is braver and ascends to the very top. Later, my story of our trip to Paris is very different to hers. My Paris is loud, street level. Young men breakdance on the hot pavement to a stereo system that takes massive batteries, while tourists gather to watch. My friend’s Paris is muted, still, distant and heat-hazed. Blue/yellow glass and white stone reflect the sun. Our descriptions of ‘Paris’ are different because our experiences were different.

The infinite variety in interpretation coupled with the sheer volume of past events means that there can be no single, definitive re-telling of history. The result is a wide range of differing interpretations and narratives about the past, even when presented with the same primary sources to analyse. Based on the assumption of multiple interpretations of past events, Keith Jenkins describes history as a “personal construct” in his book, Re-Thinking History (Jenkins, 2003, p.14). We look at the past through our own individual lens, bringing our assumptions, knowledge, understanding and attitudes about the world to create a historical narrative that is particular to our personal interpretation of the information we have gathered. Same Paris, different description.

We might gather some of that information from an archive – as the young people of Caldicott School have during their discussions of slavery and the life of Nathaniel Wells. The central role of any archive is to acquire, conserve/preserve, catalogue and make accessible primary source material. In the case of a film archive, that material might be film, video, digital media, and paper or electronic information relating to the production of the moving image media. Derrida argues that the process of archiving “produces as much as records the event" (Derrida, 1998, p.17), since the archives represent a selection of recordings about the past. While we rely on the archives to inform us about the past, through their collections, it is worth remembering that not everything that has ever happened has been recorded – on film or in any other way. Furthermore, not everything that has been recorded, has been handed to an archive to preserve for the future. The archives are not complete records of historical events, but fragments of the past that we must combine and interpret to create a history. There is no guarantee that the picture built from archive material will be complete, nor of its accuracy or inherent ‘truth’. Since we each then interpret this information, the result is a subjective description of a chronicle of events, a story about the past. My Paris is loud, youthful, vibrant.

The pupils at Caldicott School have combined two different perspectives on sugar, using images from the archives, to create a compelling animation that makes me think about how we understand the past. Both are ‘true’ representations of moments in history, but neither gives us the full picture. So what are we to make of the imagery? In the foreground we see the young boy with his - mother? Grandmother? Auntie? I assume a familiarity that isn’t present in the text. Something about the way they share. My analysis of their relationship is as much a function of my own understanding of family as it is a response to the image. Other viewers may make alternative assumptions.

The pair are ‘taking tea’ – that most British of activities, itself evocative of the colonies and an Imperial past. Sugar is sprinkled on a bowl of cereal – an American invention, a symbol of opulence and convenience, perhaps out of place in the working class parlour, which I have already assumed is where the woman and young boy are seated. The liberal, post-rationing, spoonful suggests the 1950s. The smiles on the faces of our tea-drinking pair show enjoyment. Sugar for the characters in this archive narrative means pleasure. The delight of added sweetness after the austerity of ration books, queues at the grocers, going without.

The contrast between fore and background is stark. The close up framing gives way to a very long shot of the plantation workers bent double, under the bright white sky and in the sparse shadow of palm trees. The cane is being cut in the distance, beyond a carpet of chaff across which rides a foreman on horseback. Work yet to be done. A man quenches his thirst from a large jug. No tea service, silver spoon. Sugar on the plantation is back-breaking. The image of sugar here represents exhaustion, slavery, injustice. A hand reaches through the frame, piling sugar into a brightly coloured bowl. The cheerful pink and blue of the foreground obscures and overcomes the intensity of the plantation in the background.

And repeat.

References

Derrida, J. (1998) Archive Fever. A Freudian Impression. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Jenkins, K. (2003) Re-Thinking History. London: Routledge.